The Kharadron Overlords can turn any disaster into profit, and the Mortal Realms are full of disasters of late – as one unfortunate sky-Captain discovers in the latest short story…

Garni Bengsson’s head was spinning. He felt as if he were caught in some unpleasant nightmare; at any moment, he would wake up and discover that the last few wind-seasons had been nothing but a figment of his imagination.

They had withdrawn his commission. They had revoked his shipping licence and frozen his aether-shares. He was no longer a Captain of the sky-fleets. He was no longer anything at all. Thirty years of loyal service to Barak-Nar, swept away by a single mistake. But then, had it even been an error? Even if he had to go through it all again, what could he do differently? Even a Frigate could not outrun an arcane storm that fast – or that malevolent.

The tankard of ale in front of him sat untouched. He couldn’t bring himself to take a single draught. He felt sick. He didn’t hear the copperhat at first. It took the duardin leaning down and tapping him on the chest with his cudgel before Bengsson realised he was being addressed. He blinked up at the patrolman, who was wearing the familiar peaked helmet and leather breastplate of his office. His puggish, oft-broken nose and sour expression did not suggest a comradely attitude.

‘What is it?’ said Bengsson. The duardin bristled at his tone.

‘You’re to move on,’ he growled. ‘Sharpish, if you please.’

‘I’m… what?’

That ironoak cudgel tapped menacingly on the tabletop.

‘The Lucky Shot is reserved for officers,’ the shore-guard said.

Another punch to the gut, and one Bengsson had somehow not anticipated. He felt the colour rising in his cheeks as nearby patrons turned to look at him – veterans and old fleethands with whom he would have clinked glasses and swapped tales of aeronautical derring-do just a few weeks back. Looking at them now, he saw nothing but an infuriating combination of pity and scorn.

‘What are you gruzzoks staring at?’ he growled. ‘Which one of you called the copperhats, eh? Didn’t have the nerve to tell me to my face I’m not wanted?’

‘You’ve lost your commission, Garni,’ said a black-bearded duardin leaning against the bar, surrounded by a cadre of peers. ‘Don’t make a spectacle of yourself. Rules are rules, and the Code is the Code.’

‘Is that so, Captain Humbolt?’ Bengsson said.

‘These are dangerous times,’ the other duardin replied. ‘And we can’t afford recklessness or waste. Not if Barak-Nar’s going to keep a steering hand on the Geldraad. You lost an entire shipment of processed aether-gold, along with all your escorts and two high-ups in the Aether-Khemists Guild. You’re lucky they didn’t shave your damned beard off.’

Bengsson felt that old, dangerous smile creep across his face. It was the one his Arkanaut squadmates used to say he wore in battle, when the aethershot started flying and the blood started flowing. He hadn’t worn it in a long time. Not since he’d earned his colours.

‘Care to say that again?’ he said, surprised by how calm his words sounded.

Humbolt made it halfway through his response before Bengsson crossed the distance between them, seized him by the throat and smashed a bottle of Amber Sunrise over his head.

What followed was little more than a blur, but when Bengsson regained consciousness in a holding chamber over at the portside brig, he was informed that it had taken an entire squad of guardsmen and a rather flustered bartender to prevent him from choking Captain Humbolt to death with his own beard. For his part, Bengsson was now nursing a broken wrist, two missing teeth and the worst headache he’d ever known in his life.

‘You certainly make a powerful first impression, Master Bengsson.’

The speaker swam blurrily into focus – a grizzled, scarred rogue in a battered sky-suit criss-crossed by bandoliers. He sat on the other side of the bars, smoking a pipe and gazing at Bengsson with a calculating expression. He wore no Barak-Nar insignia, and it was hard to tell whether he was a soldier, an endrineer or an officer. Bengsson wondered if he was Grundcorps, but the gun-lovers tended to keep their armour pristine and polished. This character certainly did not; his chestplate bore the scratches and pockmarks of recent action.

‘Name’s Meransson,’ the stranger said at last. ‘Albas Meransson.’

Bengsson immediately leaned forward.

‘Ah,’ the duardin smiled. ‘I see you've heard my name.’

‘I have. You’ve been cultivating quite the reputation, you and your Vongrim ship-claimers. As far as the Admirals Council is concerned, you’re little more than pirates.’

Meransson smiled. ‘Aye, that’s what they say. But then, the Council also took your commission away and grounded one of their best officers in the process, so the question is: how much do you give a kraz what those old fools think?’

‘Doesn’t much matter what I think,’ sighed Bengsson. ‘I’m done. I’ll never command a sky-ship again. I’m right back at the bottom of the ladder, and there I’ll stay.’

Meransson exhaled a great cloud of bluish smoke.

‘That’s the way it used to work,’ he said. ‘But times are changing, Garni Bengsson. There’s plenty of old sky-hands like yourself who have had their livelihoods destroyed through circumstances out of their hands. Barak-Urbaz was smashed out of the damned clouds, and they’re still talking like the old rules apply. Truth is, we haven’t seen skies this treacherous since the Garaktormun. Even Zilfin’s best can’t keep their cargo airborne when they’re smashed astern by a gale of thaggoraki sorcery.’

He paused to take a long drag on his pipe.

‘And yet,’ Meransson went on, filling the cell with smoke, ‘the Geldraad’s so fixated on shoring up the shattered market, they’re letting good duardin slide through the gaps.’

‘What are you saying?’

‘I’m saying there’s another way. I’m offering you work. Honest work.’

Seeing that Bengsson was about to speak, Meransson held up a hand.

‘Let me say my piece. The Vongrim is not technically a sanctioned guild. We don’t have access to the latest aether-tech and we can’t pay a sky-fleet officer’s salary. What we do is hard and dangerous. We seek salvage in the deadliest places in the realms, often deep behind enemy lines. I can’t offer you the prospect of your own ship. Not yet, at least. You’ll be back to slugging it out as a groundpounder, and not every shipless ex-captain is prepared for that.’

‘Not much of a sales pitch so far.’

Meransson chuckled, but his expression soon became serious again.

‘What I can offer you is this: a fair percentage and an oath that the Vongrim will always have your back. We look out for each other. We don’t scrawl through the Code looking for loopholes that’ll let us cut a brother or sister loose. So what do you say?’

For the first time, Garni Bengsson felt the weight of shame and regret lifting from him just a little. He felt something that might even be hope. Wincing, he rose to his feet and approached the bars, thrusting his good hand out. Meransson took it in a firm grip, and that was that.

‘Just one thing,’ Bengsson said. ‘How am I going to get out of the can?’

‘Don’t worry about that. We’ll take the grudge-price out of your first month’s pay.’

They watched the skyship plunge through the ruin-clouds, trailing smoke.

‘Ship’s doomed,’ said Jovial Jedreg, so named because he possessed all the easy-going charm of a bull megalofin with a harpoon lodged in its backside. Despite the duardin’s trademark pessimism, Bengsson thought that this time the old grumbler was right.

The vessel – a Barak-Zilfin ship, judging by its sky-blue markings – had been hit by a piece of ratman artillery, sending it into a death-dive. More green-white flashes of lightning speared up from the far wall of the canyon and struck her hull even now. Figures spilled from her gunwales, flailing helplessly until they passed out of sight.

‘Who flies across the Rusted Wastes without an escort?’ wondered Rulla.

‘A captain who’s been blown off course,’ said Stenni Stonearm. ‘Or whose fuel reserve’s been bokked. It happens. It’s why we’re on this salvage mission in the first place, aye?’

‘Whoever they are, they’re good,’ said Bengsson, feeling a stab of mournful nostalgia despite himself.

It had been a long time since he’d handled a ship’s wheel, but even when he’d been at the height of his power, he wasn’t sure whether he could have brought that stricken vessel down without killing everyone on board. Yet somehow the Frigate’s captain managed it, just about stalling the violent spin and levelling out before the airship’s keel struck the valley floor. The manoeuvre nullified enough of the ship’s momentum to prevent the hull from crumpling on impact. Instead, the Frigate carved a furrow of dust and splintered rock across the mountainside. The Vongrim watched from their perch some fifty metres above as it came to a smoking halt. For a moment, all was silent, as if the realm was holding its breath in the wake of the thunderous cacophony.

Then came the repellent chatter of verminous voices. Ratmen came swarming from cracks in the canyon walls, falling upon the stricken airship like bugs on a corpse. The clean snap-crack of aethershot rifles told the Vongrim that at least some of the Frigate’s crew were still in fighting shape. But they wouldn’t last long with that amount of attention.

‘What’s the plan, chief?’ asked Stenni.

Bengsson checked his pistol’s charge.

‘The plan is to get down there and kill as many thaggoraki as we can. Get the crew clear and see what we can salvage in the process. Any questions?’

Rulla grinned. ‘Does that Frigate count as part of our reclamation contract now?’

‘I’m not a Codewright, Rulla. Thank the Great Maker. Let’s save what we can first, then we’ll iron out the details.’

And with that, he hurled himself into empty air.

He plunged, weighted down by the endrin strapped to his back, letting his gyro-stabilisers keep his descent even. Far below, but rushing closer by the second, was the crashed skyship. It was a buckled mass of burning metal, but he saw figures clustered in a circle on the foredeck, crouching behind whatever meagre cover they could find. At the other end of the vessel, half a dozen Skaven gunnery teams equipped with cumbersome rotary cannons were spraying a ferocious hail of green bullets at them. Ratmen wielding swords and spears were creeping closer and closer to the cornered crew. The corpses of both duardin and thaggoraki already littered the wreckage from end to end.

Those gunners would die first, Bengsson decided.

At thirty metres up, he fired his jump-rig, and the sudden buoyancy of the aether-powered sphere slowed his fall, allowing him to find purchase on a spar of rock protruding from the cliffside. He kicked off, angling his descent so that he was positioned right above his quarry. The smoke of the Frigate’s blazing main endrin and the deafening sound of warpfire and aethershot had obscured the salvagers’ approach. Not one of the ugly creatures looked up until it was too late.

Bengsson’s first pistol blast turned the rearmost gunner’s head into a splattered mess. The rest of the Skaven screeched in surprise, eyes bulging as they saw the company of endrin-strapped duardin about to crash amongst them, but with their clumsy metal hoppers and oversized weapons, they could hardly flee in time. Bengsson landed on top of another rat, his sheer weight crushing the wretch’s spine with a satisfying crunch. Shock-absorbing mag-boots absorbed the kinetic force, and before his foes could react, Bengsson was swinging his war-hook out to drag aside the rotary barrel of another weapon. It spat a stream of bullets just past his head, rattling his skull and painfully popping his ears. Then Stenni Stonearm slammed down next to the shooter and buried a cutlass in the Skaven’s back.

‘Good work,’ Bengsson shouted, emptying his pistol into another ratman and sending it flying over the vessel’s gunwale in a spray of gore. In the blink of an eye, most of the chain-gunners were dead and the rest were in flight. The thaggoraki, perhaps not realising how few their attackers were in number, now hesitated. In doing so, they gave the Frigate’s crew the chance to counter-attack. Arkanauts leapt from cover and charged, meeting their enemies with pistol and cutlass.

‘Kill ’em all!’ roared a red-haired figure clad in a Captain’s flight suit, whose right leg was mangled so badly that it was a damned miracle she was still conscious. She was firing a long-barrelled repeater with one hand and using a boarding pole as a crutch with the other. ‘For Barak-Zilfin, and for the Cloud Traveller!’

That last was the Frigate’s name, Bengsson supposed. He recognised both the anguish and the rage in the captain’s cry. For now, the desperate adrenaline of the moment was keeping her going, but later, the realisation that her life would never be the same would hit her like a forge-piston. He – more than anyone – sympathised.

‘Get ye gone, you devils!’ Jovial Jedreg roared, blasting away with his aethershot rifle and looking as though he was enjoying himself for once.

The Skaven soon broke, as Bengsson had anticipated, falling over themselves to evade the wrath of this new and unexpected threat. The Vongrim slew as many as they could as they ran, but Bengsson called off any pursuit. The thaggoraki had a nasty talent for turning the tables on those who thought them vanquished. He made for the wounded captain, who had slumped down against the gunwale, bloodshot eyes scanning the broken ruin of her vessel. He crouched down next to her.

‘We should salvage what we can and get going before they come back,’ Bengsson said. ‘We might have sent them packing, but as soon as they realise how few we are, they’ll bring out their heavy guns and that’ll be that. We’ve got a cargo-cutter hidden a few leagues away, and we can take you all as far as the nearest wind-station.’

‘They’ll ground me for this,’ she groaned. ‘The Cloud Traveller was fresh out of the Zilfin docks. She was one of the new models, with a built-in aether refiner and the latest Iggrind-Kaz turbines. She was a beauty. Priceless. And I lost her and half my crew.’

‘I’ve seen some flying in my time,’ said Bengsson. ‘I used to be a Frigate skipper myself. I was good. But if it’d been me in your place, I doubt I’d have brought her down in one piece. You did what you could.’

‘That won’t be enough for the Council.’

Bengsson shrugged. ‘Your hold’s intact. My crew can extract most of your fuel reserves and whatever else you’re carrying. Judging from what I’ve seen, there’s a decent score there. We’ll take our cut, of course, but nothing extortionate. I’m no Barak-Mhornar cutthroat. You won’t be coming back empty-handed.’

She scrabbled at the stowage bag strapped to her wounded leg, wincing as she pulled out a stoppered flask. As she opened it and took a draught, Bengsson caught the rich, smoky scent of Zilfin ‘endrin oil’. She offered him a swig, and he took it. It burned nicely as it slipped down.

‘Even if what you say is true,’ she sighed, ‘I lost my command. The aether-gold we’ve got left in the hold won’t erase that stain. I’ll be lucky if they demote me to the companies.’

‘What’s your name?’ Bengsson asked.

‘Kelfjaar. Mora Kelfjaar.’

‘Well, Captain Kelfjaar, even if they strip it all from you, take it from me: you’re not done. The way things are now, we need skilled officers like you more than ever. Get yourself back to Barak-Zilfin and sit through whatever trumped-up show trial they arrange for you. Speak your piece, grind your teeth and suffer through it. If you get to keep your commission, all to the good. If you don’t, and they ground you, you march into the Vongrim guild-quarters on Siphoner’s Street and you tell them Garni Bengsson sent you.’

She eyed him – dubious, but with the faintest glimmer of optimism. He held out a hand and helped her clamber to her feet, supporting her on that nasty broken leg.

‘Time to leave,’ he said. ‘We can discuss my compensation for the rescue on the way.’

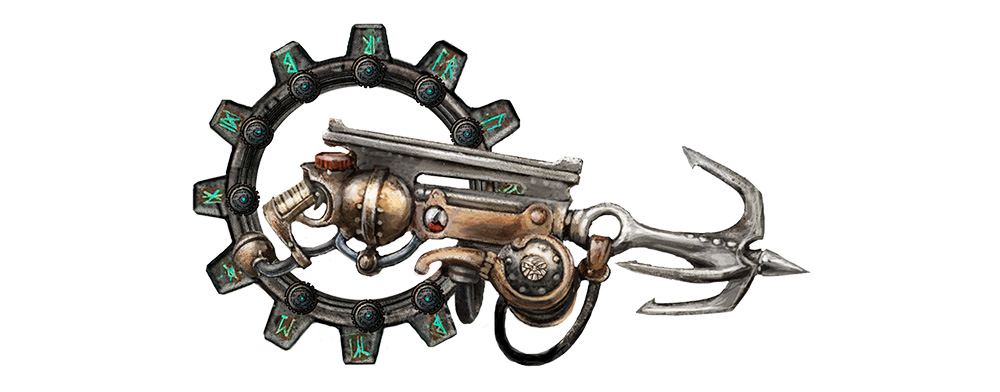

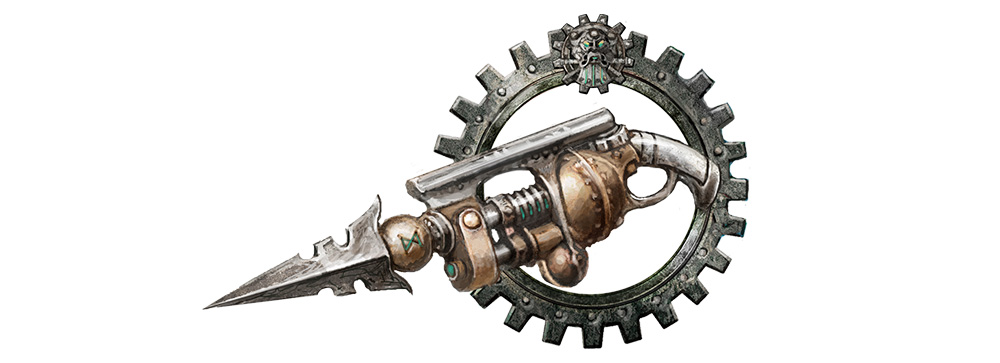

The Vongrim Harpoon Crew will be arriving at the pre-order sky-ports this Saturday, along with a new Battletome: Kharadron Overlords, as the Code demands.